The endothelium (pl.: endothelia) is a single layer of squamous endothelial cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels.[1] The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the vessel wall. Endothelial cells form the barrier between vessels and tissue and control the flow of substances and fluid into and out of a tissue.

| Endothelium | |

|---|---|

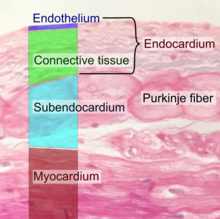

Diagram showing the location of endothelial cells | |

Transmission electron micrograph of a microvessel showing endothelial cells, which encircle an erythrocyte (E), forming the innermost layer of the vessel, the tunica intima. | |

| Details | |

| System | Circulatory system |

| Location | Lining of the inner surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels |

| Identifiers | |

| MeSH | D004727 |

| TH | H2.00.02.0.02003 |

| FMA | 63916 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

Endothelial cells in direct contact with blood are called vascular endothelial cells whereas those in direct contact with lymph are known as lymphatic endothelial cells. Vascular endothelial cells line the entire circulatory system, from the heart to the smallest capillaries.

These cells have unique functions that include fluid filtration, such as in the glomerulus of the kidney, blood vessel tone, hemostasis, neutrophil recruitment, and hormone trafficking. Endothelium of the interior surfaces of the heart chambers is called endocardium. An impaired function can lead to serious health issues throughout the body.

Structure

The endothelium is a thin layer of single flat (squamous) cells that line the interior surface of blood vessels and lymphatic vessels.[1]

Endothelium is of mesodermal origin. Both blood and lymphatic capillaries are composed of a single layer of endothelial cells called a monolayer. In straight sections of a blood vessel, vascular endothelial cells typically align and elongate in the direction of fluid flow.[2][3]

Terminology

The foundational model of anatomy, an index of terms used to describe anatomical structures, makes a distinction between endothelial cells and epithelial cells on the basis of which tissues they develop from, and states that the presence of vimentin rather than keratin filaments separates these from epithelial cells.[4] Many considered the endothelium a specialized epithelial tissue.[5]

Function

The endothelium forms an interface between circulating blood or lymph in the lumen and the rest of the vessel wall. This forms a barrier between vessels and tissues and control the flow of substances and fluid into and out of a tissue. This controls the passage of materials and the transit of white blood cells into and out of the bloodstream. Excessive or prolonged increases in permeability of the endothelium, as in cases of chronic inflammation, may lead to tissue swelling (edema). Altered barrier function is also implicated in cancer extravasation.[6]

Endothelial cells are involved in many other aspects of vessel function, including:

- Blood clotting (thrombosis and fibrinolysis). Under normal conditions, the endothelium provides a surface on which blood does not clot, because it contains and expresses substances that prevent clotting,[7] including heparan sulfate which acts as a cofactor for activating antithrombin, a protein that inactivates several factors in the coagulation cascade.[8]

- Inflammation.[9] Endothelial cells actively signal to white blood cells of the immune system[10] during inflammation

- Formation of new blood vessels (angiogenesis).

- Constriction and enlargement of the blood vessel, called vasoconstriction and vasodilation, and hence the control of blood pressure

Blood vessel formation

The endothelium is involved in the formation of new blood vessels, called angiogenesis.[11] Angiogenesis is a crucial process for development of organs in the embryo and fetus,[12] as well as repair of damaged areas.[13] The process is triggered by decreased tissue oxygen (hypoxia) or insufficient oxygen tension leading to the new development of blood vessels lined with endothelial cells. Angiogenesis is regulated by signals that promote and decrease the process. These pro- and antiangiogenic signals including integrins, chemokines, angiopoietins, oxygen sensing agents, junctional molecules and endogenous inhibitors.[12] Angiopoietin-2 works with VEGF to facilitate cell proliferation and migration of endothelial cells.

The general outline of angiogenesis is

- activating signals binding to surface receptors of vascular endothelial cells.

- activated endothelial cells release proteases leading to the degradation of the basement membrane

- endothelial cells are freed to migrate from the existing blood vessels and begin to proliferate to form extensions towards the source of the angiogenic stimulus.

Host immune response

Endothelial cells express a variety of immune genes in an organ-specific manner.[14] These genes include critical immune mediators and proteins that facilitate cellular communication with hematopoietic immune cells.[15] Endothelial cells encode important features of the structural cell immune response in the epigenome and can therefore respond swiftly to immunological challenges. The contribution to host immunity by non-hematopoietic cells, such as endothelium, is called “structural immunity”.[16]

Clinical significance

Endothelial dysfunction, or the loss of proper endothelial function, is a hallmark for vascular diseases, and is often regarded as a key early event in the development of atherosclerosis.[17] Impaired endothelial function, causing hypertension and thrombosis, is often seen in patients with coronary artery disease, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, as well as in smokers. Endothelial dysfunction has also been shown to be predictive of future adverse cardiovascular events including stroke, heart disease, and is also present in inflammatory disease such as rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and systemic lupus erythematosus.[18][19]

Endothelial dysfunction is a result of changes in endothelial function.[20][21] After fat (lipid) accumulation and when stimulated by inflammation, endothelial cells become activated, which is characterized by the expression of molecules such as E-selectin, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1, which stimulate the adhesion of immune cells.[22] Additionally, transcription factors, which are substances which act to increase the production of proteins within cells, become activated; specifically AP-1 and NF-κB, leading to increased expression of cytokines such as IL-1, TNFα and IFNγ, which promotes inflammation.[23][24] This state of endothelial cells promotes accumulation of lipids and lipoproteins in the intima, leading to atherosclerosis, and the subsequent recruitment of white blood cells and platelets, as well as proliferation of smooth muscle cells, leading to the formation of a fatty streak. The lesions formed in the intima, and persistent inflammation lead to desquamation of endothelium, which disrupts the endothelial barrier, leading to injury and consequent dysfunction.[25] In contrast, inflammatory stimuli also activate NF-κB-induced expression of the deubiquitinase A20 (TNFAIP3), which has been shown to intrinsically repair the endothelial barrier.[26]

One of the main mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction is the diminishing of nitric oxide, often due to high levels of asymmetric dimethylarginine, which interfere with the normal L-arginine-stimulated nitric oxide synthesis and so leads to hypertension. The most prevailing mechanism of endothelial dysfunction is an increase in reactive oxygen species, which can impair nitric oxide production and activity via several mechanisms.[27] The signalling protein ERK5 is essential for maintaining normal endothelial cell function.[28] A further consequence of damage to the endothelium is the release of pathological quantities of von Willebrand factor, which promote platelet aggregation and adhesion to the subendothelium, and thus the formation of potentially fatal thrombi.

Angiosarcoma is cancer of the endothelium and is rare with only 300 cases per year in the US.[29] However it generally has poor prognosis with a five-year survival rate of 35%.[30]

Research

Endothelium in cancer

It has been recognised that endothelial cells building tumour vasculature have distinct morphological characteristics, different origin compared to physiological endothelium, and distinct molecular signature, which gives an opportunity for implementation of new biomarkers of tumour angiogenesis and could provide new anti-angiogenic druggable targets.[31]

Endothelium in diet

A healthy diet abundant in fruits and vegetables has a beneficial impact on endothelial function, whilst a diet high in red and processed meats, fried foods, refined grains and processed sugar increases adhesion endothelial cells and atherogenic promoters.[32] High-fat diets adversely affect the endothelial function.[33]

A Mediterranean diet has been found to improve endothelial function in adults which can reduce risk of cardiovascular disease.[34][35] Walnut consumption improves endothelial function.[36][37]

Endothelium in Covid-19

In April 2020, the presence of viral elements in endothelial cells of 3 patients who had died of COVID-19 was reported for the first time. The researchers from the University of Zurich and Harvard Medical School considered these findings to be a sign of a general endotheliitis in different organs, an inflammatory response of the endothelium to the infection that can lead or at least contribute to multi-organ failure in Covid-19 patients with comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension and cardiovascular disease.[38][39]

History

In 1865, the Swiss anatomist Wilhelm His first coin the term “endothelium”.[40] In 1958, A. S. Todd of the University of St Andrews demonstrated that endothelium in human blood vessels have fibrinolytic activity.[41][42]

See also

- Apelin

- Caveolae

- Cellular dewetting

- Endothelial activation

- Endothelial microparticle

- Endothelial progenitor cell

- Endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF)

- Robert F. Furchgott (1998 Nobel prize for discovery of EDRF)

- Platelet activation

- Susac's syndrome

- Tunica intima

- VE-cadherin

- Weibel–Palade body

- Angiocrine growth factors

- Endothelial Cell Tropism

References

External links

- Anatomy photo: Circulatory/vessels/capillaries1/capillaries3 - Comparative Organology at University of California, Davis, "Capillaries, non-fenestrated (EM, Low)"

- Histology image: 21402ooa – Histology Learning System at Boston University