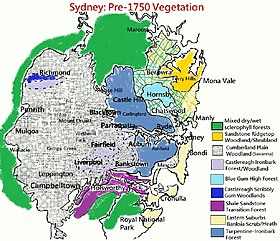

The ecology of Sydney, located in the state of New South Wales, Australia, is diverse for its size,[1] where it would mainly feature biomes such as grassy woodlands or savannas and some sclerophyll forests, with some pockets of mallee shrublands, riparian forests, heathlands, and wetlands, in addition to small temperate and subtropical rainforest fragments.[2][3]

There are 79 vegetation communities in the Sydney metropolitan area that are identified, described and mapped.[4] The combination of climate, topography, moisture, and soil influence the dispersion of these ecological communities across a height gradient from 0 to 200 metres (0 to 700 ft).[5] There are many hiking trails, paved and unpaved roads for exploring the many different biomes and ecosystems.[6][7][8]

Savannas (or grassy woodlands), the most predominant biome in the Sydney region,[9] mainly occur in the Cumberland Plain west of Sydney CBD, which generally feature eucalyptus trees that are usually in open, dry sclerophyll woodland areas with shrubs (typically wattles, callistemons, grevilleas and banksias) and sparse grass in the understory, reminiscent of Mediterranean forests.[10] The plants in this community tend to have rough and spiky leaves, as they are grown in areas with low soil fertility.

Wet sclerophyll forests, which are part of Eastern Australian temperate forests, have narrow, relatively tall, dense trees with a lush, moist understory of fleecy shrubs and tree ferns. They are mainly found in the wetter areas, such as Forest District and the North Shore.[11]

It has been calculated that around 98,000 hectares of native vegetation remains in the Sydney metropolitan area, shaping the geography of Sydney, about half of what is likely to have been existing at the time of European arrival.[12]

Historical descriptions

General topographical descriptions

In 1787, the First Fleet personnel discovered a landscape that was alien to them, and unlike the green meadows and deciduous forests of England. Arthur Phillip expressed that:[13]

The coast, as well as the neighbouring country in general, is covered with wood...The necks of land that form the coves are mostly covered with timber, yet so rocky that it is not easy to comprehend how the trees could have sufficient nourishment to bring them to so considerable a magnitude.

This was a response to comparisons with the mostly deeper, fertile soils of the British Isles and how the rocky mountainous areas like the Scottish Highlands and Dartmoor lacked tree cover.[13]

The "neck of land" which separates the southern part of the harbour from the was primarily sand. Between Sydney Cove and Botany Bay the first area is made up of woodland. The rest of the land consisted of heath, poor sand and several swamplands. Coastal areas featured mangroves in many inlets, estuaries at Port Jackson, in addition to decentralized areas of saltwater or freshwater marshes, and sheltered areas of subtropical rainforest along waterbody valleys.[13]

Most of the North Shore and inland areas featured sclerophyll forests and woodlands filled with eucalypts of many different species, ranging in different heights, and growing at immensely contrasting densities. Much of the wooded land had grass cover under the trees, but comparatively small understorey shrub or smaller tree growth. Cumberland Plain, which is inland, had sparser and fewer tree cover than the region near the coast. By May 1789 much of the thick forest around Port Jackson was cleared.[13]

First Fleet surgeon George Worgan described the environment of Sydney, particularly its terrain:[13]

...We meet with, in many parts, a fine black soil; luxuriantly covered with grass, & the Trees at 30 or 40 yards [27–37 m] distant from each other, so as to resemble Meadow land, yet these spots are frequently interrupt[ed] in their Extent by either a rocky, or a sandy, or a swampy surface, crowded with large trees, and almost impenetrable from Brushwood which being the case will necessarily require much Time and Labour to cultivate any considerable space of land together.

In 1819, British settler William Wentworth described Sydney's vegetation and landform in great detail:

The colony of New South Wales possesses every variety of soil, from the sandy heath, and the cold hungry clay, to the fertile loam and the deep vegetable mould. For the distance of 5 mi (8.0 km) to 6 mi (9.7 km) from the coast, the land is in general extremely barren, being a poor hungry sand, thickly studded with rocks. A few miserable stunted gums, and a dwarf underwood, are the richest productions of the best part of it; while the rest never gives birth to a tree at all, and is only covered with low flowering shrubs, whose infinite diversity, however, and extraordinary beauty, render this wild heath the most interesting part of the country for the botanist, and make even the less scientific beholder forget the nakedness and sterility of the scene.

Beyond this barren waste, which thus forms a girdle to the coast, the country suddenly begins to improve. The soil changes to a thin layer of vegetable mould, resting on a stratum of yellow clay, which is again supported by a deep bed of schistus. The trees of the forest are here of the most stately dimensions. Full sized gums and iron barks, alongside of which the loftiest trees in this country would appear as pigmies, with the beefwood tree, or as it is generally termed, the forest oak, which is of much humbler growth, are the usual timber. The forest is extremely thick, but there is little or no underwood.

At this distance, however, the aspect of the country begins rapidly to improve. The forest is less thick, and the trees in general are of another description; the iron barks, yellow gums, and forest oaks disappearing, and the stringy barks, blue gums, and box trees, generally usurping their stead. When you have advanced about 4 mi (6.4 km) further into the interior, you are at length gratified with the appearance of a country truly beautiful. An endless variety of hill and dale, clothed in the most luxuriant herbage, and covered with bleating flocks and lowing herds, at length indicate that you are in regions fit to be inhabited by civilized man. The soil has no longer the stamp of barrenness. A rich loam resting on a substratum of fat red clay, several feet in depth, is found even on the tops of the highest hills, which in general do not yield in fertility to the valleys. The timber, strange as it may appear, is of inferior size, though still of the same nature, i. e. blue gum, box, and stringy bark. There is no underwood, and the number of trees upon an acre do not upon an average exceed thirty. They are, in fact, so thin, that a person may gallop without difficulty in every direction.[14]

Positive

Early settlers compared the landscapes to the manicured parks of England which also featured well-spaced trees and a grassy understorey.[15] In 1787, Arthur Bowes Smyth from the First Fleet described the landscape in a favourable manner:[13]

...fresh terraced, lawns and grottos with distinct plantations of the tallest and most stately trees I ever saw in any nobleman's grounds in England, cannot excel in beauty those whose nature now presented to our view. The singing of the various birds among the trees, the flight of the numerous parraquets, lorrequets, cockatoos and macaws, made all around appear like an enchantment; the stupendous rocks from the summit of the hills and down to the very water's edge hang'g over in a most awful way from above, and form’g the most commodious quays by the water, beggard all description.

Captain John Hunter, who criticised Sydney for having "poor, sterile soil, full of stones", had a more positive view of Rosehill's and Parramatta's landscape, which are further west, for having arable lands, stating:[13]

...But near, and at the head of the harbour, there is a very considerable extent of tolerable land, and which may be cultivated without waiting for its being cleared of wood; for the trees stand very wide of each other, and have no underwood: in short, the woods on the spot I am speaking of resemble a deer park… but the soil appears to me to be rather sandy and shallow, and will require much manure to improve it… however, there are people… who think it good land… The grass upon it is about 3 feet [nearly a metre] high, very close and thick; probably farther back there may be very extensive tracts of this kind of country…

Another First Fleet surgeon, Arthur Bowes Smyth, also acknowledged the beauty of scenery:[13]

The general face of the country is certainly pleasing, being diversified with gentle scents, and little winding vallies, covered for the most part with large spreading trees, which afford a succession of leaves in all seasons. In those places where trees are scarce, a variety of flowering shrubs abound, most of them entirely new to an European and surpassing in beauty, and number, all I ever saw in an uncultivated state.

In 1827, Peter Cunningham described the western plains of Sydney as "a fine timbered country, perfectly clear of bush...through which you might, generally speaking, drive a gig in all directions, without any impediment in the shape of rocks, scrub or close forest.".[16]

Negative

After landing, the First Fleet thought that Botany Bay was an inhospitable, swampy piece of land which lacked a source of drinking water, in addition to the area featuring poor, sandy soils that did not have any substance. Arthur Phillips writes:[13]

The appearance of the place is picturesque and pleasing...but something more essential than beauty of appearance...must be sought in a place where the permanent residence of multitudes is to be established.

Regarding Phillips' statement, Australian environmentalist Tim Flannery wrote: "The vegetation the early Europeans found growing on the Sydney sandstone both delighted and appalled them...the hungry settlers realized in despair that this magnificent vegetation offered little sustenance". Moreover, the First Fleet's reaction to the Botany Bay area was so negative that Phillip and his crew almost instantly explored further north, towards Port Jackson and Broken Bay.[13]

Upon arriving in Port Jackson, First Fleet lieutenant David Blackburn wrote that Sydney Harbour was "either Immense Barren Rocks, tumbled together in Large Ridges which are almost Inaccessible to Goats, or A Dry Sandy Soil and A General Want of Water". First Fleet officer John Hunter also described Sydney Cove as "very bad, most of the ground being covered with rocks, or large stones".[13]

In July 1788, Lieutenant Ralph Clark, a member of the First Fleet, had a scathing view of Sydney's landscape, climate and as well its inhabitants, writing:[13]

I shall only tell you that this is the poorest country in the world, which its inhabitance [sic] shows they are the most miserable set of wretches under the Sun… there is neither river or Spring in the country that we have been able to find… all the fresh water comes out of swamps which the country abounds with… the country is overrun with large trees not one Acre of clear ground to be seen… the Thunder and Lightning is the most Terrible I ever herd [sic], it is the opinion of every body here that the Government will remove the Settlement to some other place for if it remains here this country will not be able to maintain its self in 100 years...

In a 1793 commentary map by Watkin Tench, the overall notion was that most of Sydney agriculturally poor – The land around South Head was "exceedingly rocky, sandy & barren"; the area northwest of Botany Bay was "sandy barren swampy Country"; the coastline from Manly to Mona Vale was "sandy, rocky and very bad Country", the Ku-ring-gai Chase area was "very bad & rugged", the Cattai area was "very dreadful Country", and the southwest of Prospect Hill was a "bad Country frequently over-flowed".[13]

Biomes

- Rainforests

- North Coast Warm Temperate Rainforests – Dominated by Ceratopetalum apetalum, Doryphora sassafras and Acmena smithii, it is scarcely present in the RNP and Hacking River valley in around Sutherland in southern Sydney, and predominant in the Ku-ring-gai Chase National Park and Turramurra in Northern Sydney, near Hornsby.[17]

- Dry Rainforests or Western Sydney Dry Rainforest – It is very thinly distributed across the dry areas to the south of Blue Mountains and in small portions in Calmsley Hill Farm in Western Sydney Parklands, near Abbotsbury, New South Wales, and as well as in the Camden area, but in fragments. They have Alectryon subcinereus as one of the tree covers and Clerodendrum tomentosum as shrubby covers.[18]

- Littoral Rainforests – Dominated by Acmena smithii, Ficus rubiginosa, and Elaeodendron australe, it occurs in sporadic areas in northern Illawarra to Royal National Park (near Bundeena and in Towra Point Nature Reserve in Sutherland Shire), and also in one diminutive area in Northern Beaches Council (Mona Vale) in the Northern Suburbs to Newcastle.[19]

- Wet scleropyhll forests

- North Coast Wet Sclerophyll Forests – Dominated by tall Eucalyptus saligna and Eucalyptus pilularis, karrabina, peppermints, Eucalyptus oreades and Eucalyptus globulus, and receiving high amount of rainfall (above 1000 mm), it is present in Ku-ring-gai Council, Hornsby Shire, Narrabeen, Lane Cove, Pennant Hills and Castle Hill in the north, and in the Illawara region, with small portions in Ryde, North Parramatta and Pittwater.[20][21][22]

- The Blue Gum High Forest – Strictly found in northern parts of Sydney, it is a wet sclerophyll forest where the annual rainfall is over 1100 mm (43 in), with its trees between 20 and 40 metres tall.[23]

- Northern Hinterland Wet Sclerophyll Forests – Dominated by Eucalyptus resinifera and Syncarpia glomulifera, it was once extensive on the north shore across the local government areas of Hornsby, Ku-ring-gai, Ryde, Willoughby, Lane Cove, Parramatta, Baulkham Hills and Blacktown to the north of Sydney, with small outliers in Menai, Bankstown and Auburn in the southwest.[24][25]

- Sydney turpentine ironbark forest – Characterized by thick shrubs and dominated by Syncarpia glomulifera, it is a tall open forest with trees as high as 30 metres and is found on shale and shale-meliorated soils found in small pockets at Campbelltown, Heathcote and Menai.[26][27]

- Southern Lowland Wet Sclerophyll Forests – Containing Corymbia maculata, it is found in upper Narrabeen, Pittwater, Woronora and Illawara, as well as on the foreshores of Hacking, Parramatta and Georges Rivers.[28]

- North Coast Wet Sclerophyll Forests – Dominated by tall Eucalyptus saligna and Eucalyptus pilularis, karrabina, peppermints, Eucalyptus oreades and Eucalyptus globulus, and receiving high amount of rainfall (above 1000 mm), it is present in Ku-ring-gai Council, Hornsby Shire, Narrabeen, Lane Cove, Pennant Hills and Castle Hill in the north, and in the Illawara region, with small portions in Ryde, North Parramatta and Pittwater.[20][21][22]

- Grassy Woodlands/Savannas

- Cumberland Plain Woodland – These are shrub and grass eucalyptus communities located in areas of low to moderate rainfall (less than 950 millimetres annually) and are most commonly found in large parts of the Sydney metropolitan area, namely in Western Sydney or the Cumberland Plain. Moist Shale Woodlands[29] also exist within this biome, but they are distinguished by their lusher plant habitats.[30] It is a dry woodland remnant containing waxy-leaved shrubs, twiners, herbs and small trees in a grassy understorey.[31] It has a number of sub-regions: Moist Shale Woodlands, Western Sydney dry rainforest, and Shale sandstone transition forest, among others.[32]

- Dry sclerophyll forests

- Sydney Coastal Dry Sclerophyll Forests – Predominant on the northeast parts of the Woronora Plateau on ridgelines within the Royal, Heathcote and Dharawal national parks and Garawarra State Conservation Area in southern Sydney. It is also present in north of Sydney Harbour and extends to both sides of the Hawkesbury River in Northern Beaches and Hornsby LGA's and Pennant Hills.[33][34]

- Sydney Hinterland Dry Sclerophyll Forests – Found in the drier parts (less than 950 mm) of the Woronora Plateau, also in Appin, Sandy Point, pockets in the southwestern edges of the Cumberland Plain (on the doorsteps of the Blue Mountains), and on the foreshores of the Hawkesbury River, it features 10–25 m tall eucalyptus trees with ostensible sclerophyll shrub understorey and open groundcover of sclerophyll sedges.[35][36]

- Cooks River/Castlereagh ironbark forest – Found in Castlereagh and Holsworthy, and a few remnants in the cities of Auburn, Bankstown and Liverpool, it is an ironbark shrub-grass forest located in western Sydney that sit on gravelly-clay soils and is made up of a moderately tall open eucalyptus forest or woodland to a low compact brush of paperbarks with nascent eucalypts. Broad-leaved ironbark (Eucalyptus fibrosa) is the most commonly spotted tree.[24][37]

- Sydney Sand Flats Dry Sclerophyll Forests – Present in northern Holsworthy with smaller examples at Rookwood and Villawood and is dominated by Eucalyptus sclerophylla.[38]

- Coastal Dune Dry Sclerophyll Forests – Examples are found at Bundeena, Kurnell and La Perouse in southern Sydney containing a collection of sclerophyllous shrub and heath species and a ferny ground cover.[39]

- Heathlands

- Wallum Sand Heaths – Present in Pleistocene sand dunes sitting high on sandstone cliff tops between Bundeena in Royal NP, Woollahra, Kurnell peninsula, Narrabeen and Sydney Heads which contain Allocasuarina distyla, Banksia serrata and Banksia aemula. There are also a wide variety of woody species such as tea-trees, grevilleas, peas and wattles. The ground layer comprises on open cover of sedges and forbs.[40]

- Sydney Coastal Heaths – Found extensively in the Sydney metropolitan area and in the eastern parts of the Woronora and Hornsby plateaus particularly in Royal and Ku-ring-gai national parks with prominence of Eucalyptus luehmanniana.[41] Heaths on coastal headlands are found in and around Garie Beach on the outskirts of southern Sydney, near Royal NP.[42]

- Scrublands/Shrublands

- Elderslie Banksia Scrub Forest – A critically endangered scrubby woodland community situated in southwestern Sydney that features a variety of stunted forest or woodland found on sandy substrates associated with deep Tertiary sand deposits. It has been reduced in extent of at least 90% of its original pre-European extent.[43]

- Castlereagh Scribbly Gum and Agnes Banks Woodlands – A small scrubby woodland community found in western Sydney with vegetation comprising low woodlands with sclerophyllous shrubs and an uneven ground layer of graminoids and forbs.[44]

- Sydney Sandstone Ridgetop Woodland – A shrubby woodland and mallee community situated in northern parts of Sydney on ridgetops and slopes of the Hornsby Plateau, Woronora Plateau and the lower Blue Mountains area. It is an area of high biodiversity, existing on poor sandstone soils, with regular wildfires, and moderate rainfall.[45][46]

- Freshwater Wetlands

- Castlereagh swamp woodland – A swampy sclerophyll forest affiliated with sporadically flooded soils containing Tertiary, Holocene and Quaternary sand deposits. It is found in low-elevated areas of Liverpool and in Voyager Point, and is made up of moderate to heavy cover of paperbark trees.[41]

- Coastal Heath Swamps – Common in Holsworthy defense area, Woronora catchment area and the Hornsby plateau including Garigal and Ku-ring-gai Chase national parks.[47]

- Coastal Freshwater Lagoons – Occurs on poorly drained alluvial flats and sand depressions and may be surrounded by broad-leaved cumbungi (Typha orientalis).[48]

- Forested wetlands

- Estuarine swamp oak forest – Found on the floodplains in most parts of metropolitan Sydney near streamlines, where Casuarina glauca (swamp oak) is the dominant species.[49]

- Sydney coastal river-flat forest – Found on the river flats of the coastal floodplains in most parts of Sydney that have rivers or creeks (and as well as other regions in eastern New South Wales). They are gallery forests that prominently features tall, open eucalypts and casuarinas that stand on silt, clay-loam and sandy loam soils on sporadically flooded alluvial flats, drainage lines and river terraces associated with coastal floodplains.[50][31]

- Coastal Swamp Forests – Occupies the low-lying coastal river flats, swamps and sand depressions, which are mostly cleared from the Sydney metropolitan area, but still exist in places like Georges River National Park, Milperra, Chipping Norton, Prospect Creek and Kurnell in southeastern Sydney, and Wheeler Heights, Narrabeen and Dee Why in the Northern Beaches.[51]

- Coastal Floodplain Wetlands – They cover a series of eucalypt and casuarina dominated communities found on low-lying coastal alluvial soils, such as in Georges River and its tributaries in northern Woronora and the lowlands of Blue Mountains. They are dominated by Microlaena stipoides.[52]

- Eastern Riverine Forests – Many riparian scrubs are found on rocky creeks that are enclosed with coarse sandy alluvial deposits with common vegetation being Tristaniopsis laurina.[53]

- Saline Wetlands

- Mangrove Swamps – Found in Towra, they are a basic community dominated by either Avicennia marina or Aegiceras corniculatum.[54]

- Saltmarshes – Usually located on estuarine alluvial soils, small tracts also exist on headlands exposed to prevailing sea spray.[55]

- Seagrass Meadows – Occurring on sandy nether of coastal estuaries and bays, they include a number of subaqueous aquatic species, such as eel grass (Zostera spp) and sea grass (Posidonia australis).[56]

Complete list

Vegetation

The most widespread eucalyptus species in the Sydney region include:[34]

- Angophora costata (Sydney red gum)

- Eucalyptus amplifolia (cabbage gum)

- Eucalyptus piperita (Sydney peppermint)

- Eucalyptus sieberi (silvertop ash)

- Eucalyptus oblonga (stringybark)

- Eucalyptus capitellata (brown stringybark)

- Eucalyptus bosistoana (coast grey box)

- Eucalyptus moluccana (grey box)

- Corymbia gummifera (red bloodwood)

- Eucalyptus racemosa (snappy gum)

- Eucalyptus haemastoma (scribbly gum)

- Corymbia maculata (spotted gum)

- Eucalyptus luehmanniana (yellow top mallee ash)

- Eucalyptus eugenioides (thin-leaved stringybark)

- Eucalyptus robusta (swamp mahogany)

- Eucalyptus baueriana (round leaf box)

- Eucalyptus longifolia (woollybutt)

- Eucalyptus paniculata (grey ironbark)

- Eucalyptus punctata (grey gum)

- Eucalyptus melliodora (yellow box)

Non-eucalyptus tree species:

- Araucaria cunninghamii (hoop pine)

- Araucaria bidwillii (bunya pine)

- Corymbia eximia (yellow bloodwood)

- Allocasuarina torulosa (forest oak)

- Melaleuca linariifolia (snow-in-summer)

- Melaleuca quinquenervia (broad-leaved paperbark)

- Melaleuca alternifolia (narrow-leaved paperbark)

- Melaleuca armillaris (bracelet honey myrtle)

- Melaleuca decora (white feather honeymyrtle)

- Tristaniopsis laurina (water gum)

- Acacia falcata (sickle wattle)

- Callitris endlicheri (black cypress pine)

- Grevillea robusta (Australian silver oak)

- Acacia longifolia (Sydney golden wattle)

- Acacia podalyriifolia (Mount Morgan wattle)

- Melaleuca quinquenervia (paperbark tea tree)

- Syncarpia glomulifera (turpentine tree)

- Syzygium smithii (black cypress pine)

- Banksia integrifolia (coast banksia)

- Brachychiton acerifolius (Illawarra flame tree)

- Brachychiton populneus (kurrajong)

- Melaleuca viminalis (weeping bottlebrush)

- Cupaniopsis anacardioides (tuckeroo)

- Ficus macrophylla (Moreton Bay fig)

- Ficus microcarpa (Hill's weeping fig)

- Ficus rubiginosa (Port Jackson's fig)

- Flindersia australis (crow's ash)

- Glochidion ferdinandi (cheese tree)

- Lophostemon confertus (brush box)

Common shrub species include, but are not limited to:

- Banksia serrata (old man banksia)

- Casuarina glauca (swamp oak)

- Ceratopetalum gummiferum (New South Wales Christmas bush)

- Lomandra longifolia (spiny-head mat-rush)

- Banksia spinulosa

- Xanthosia pilosa (woolly xanthosia)

- Banksia aemula (wallum banksia)

- Banksia robur (swamp banksia)

- Melaleuca citrina (lemon bottlebrush)

- Melaleuca linearis (narrow-leaved bottlebrush)

- Dichondra repens (kidney weed)

- Centella asiatica (Asiatic pennywort)

- Veronica plebeia (trailing speedwell)

- Ozothamnus diosmifolius (rice flower)

Introduced

Introduced shrubs and/or vines that are invasive species):[57]

- Olea africana (African olive)

- Gleditsia triacanthos (honey locust)

- Thunbergia grandiflora (blue skyflower)

- Alternanthera philoxeroides (alligator weed)

- Anredera cordifolia (Madeira-vine)

- Asparagus aethiopicus (asparagus fern)

- Lantana camara (West Indian lantana)

- Cestrum parqui (green cestrum)

- Senna pendula (Easter cassia)

- Opuntia monacantha (prickly pear)

- Ligustrum sinense (small-leaved privet)

- Solanum mauritianum (wild tobacco bush)

- Ricinus communis (castor oil plant)

- Murraya paniculata (orange jasmine)

- Ipomoea cairica (Cairo morning glory)

- Araujia sericifera (cruel vine)

- Cardiospermum grandiflorum (balloon vine creeper)

- Cortaderia selloana (pampas grass)

- Ipomoea indica (purple morning glory)

- Vinca major (blue perrywinkle)

- Passiflora suberosa (corky passion vine)

Hardiness zone

Due to the microclimate, the plant hardiness zone in the Sydney area would range:[58]

- Zone 11a (4.4 to 7.2°C):

- Sydney CBD

- Sydney Harbour

- North Sydney

- Lower North Shore, which includes Mosman Bay and Chatswood

- Zone 10b (1.7°C to 4.4°C):

- Northern Beaches

- Inner West

- City of Parramatta

- Eastern portion of Canterbury-Bankstown and Cumberland City Council (or eastwards from Lidcombe and Lakemba)

- North Shore

- Eastern suburbs

- Georges River Council

- Southern Sydney

- Zone 10a (-1.1°C to 1.7°C):

- Most of Cumberland Plain, which include the cities of Fairfield, Blacktown, Penrith, Liverpool and Campbelltown

- Hornsby Shire

- Hills District

- Zone 9b (-3.9°C to -1.1°C):

- City of Hawkesbury, which includes Richmond and Windsor

- Camden Council

- Wollondilly Shire

Wildlife

The fauna of the Sydney area is diverse and its urban area is home to variety of bird and insect species, and also a few bat, arachnid and amphibian species. Introduced birds such as the house sparrow, common myna and feral pigeon are ubiquitous in the CBD areas of Sydney.[59][60] Moreover, possums, bandicoots, rabbits, feral cats, lizards, snakes and frogs may also be present in the urban environment, albeit seldom in city centers.[61]

About 40 species of reptiles are found in the Sydney region and 30 bird species exist in the urban areas.[62][63][64] Sydney's outer suburbs, namely those adjacent to large parks, have a great diversity of wildlife.[65] Since European settlement and the subsequent bushland clearing for the increasing population, 60% of the original mammals are now considered endangered or vulnerable, and many reptile species are experiencing population diminution and are becoming elusive.[66]

Tetrapods

This list includes bird species that are widespread in the Sydney metropolitan area:[67]

- Australian magpie

- Australian raven

- Australian white ibis

- Bell miner

- Common starling

- Crested pigeon

- Eastern rosella

- Eastern spinebill

- Galah

- Grey butcherbird

- Laughing kookaburra

- Magpie lark

- Masked lapwing

- Noisy miner

- Pacific koel

- Pied currawong

- Rainbow lorikeet

- Spotted dove

- Silver gull

- Sulphur-crested cockatoo

- Superb fairy-wren

- Willie wagtail

Although not commonly spotted, these birds are also present in Sydney:[64]

- Australian king-parrot

- Brown goshawk

- Common bronzewing

- Eastern yellow robin

- Golden whistler

- Little wattlebird

- Little raven

- Nankeen kestrel

- New Holland honeyeater

- Pallid cuckoo

- Peregrine falcon

- Red-browed finch

- Red wattlebird

- Red-whiskered bulbul

- Silvereye

- Tawny frogmouth

- Turquoise parrot

- Whistling kite

- White-bellied sea-eagle

This list includes mammal, reptile and amphibian species that are spotted in the Sydney urban area:[68][69]

- Australian blue-tongued skink

- Australian green tree frog

- Australian water dragon

- Bibron's toadlet

- Bleating tree frog

- Broad-headed snake

- Brush-tailed phascogale

- Bush rat

- Common bent-wing bat

- Common brushtail possum

- Common ringtail possum

- Common garden skink

- Common death adder

- Diamond python

- Eastern brown snake

- East-coast free-tailed bat

- Great barred frog

- Giant burrowing frog

- Golden bell frog

- Golden water skink

- Feathertail glider

- Grey-headed flying fox

- Leaf green tree frog

- Long-nosed bandicoot

- Squirrel glider

- Sugar glider

- Three-toed earless skink

- Yellow-bellied glider

- Peron's tree frog

- Red-bellied black snake

- Snake-eyed skink

- Three-toed earless skink

Arthropods

This list includes insect, spider and centipede species that are commonly present in Sydney:[70]

- Australian carpet beetle

- Australian garden orb weaver spider

- Australian grapevine moth

- Australian painted lady

- Bess beetle

- Black house spider

- Emperor gum moth

- Giant centipede

- Green-head ant

- Imperial hairstreak

- Christmas beetle

- Funnel ant

- Green vegetable bug

- House centipede

- Katydid

- Orchard swallowtail butterfly

- Bronze flat

- Green vegetable bug

- Redback spiders

- Pill bug

- Plague soldier beetle

- Punctate flower chafer

- Redback spider

- Skull spider

- Sydney funnel-web spider

- Sydney huntsman spider

- Spider wasp

- Transverse ladybird

- Zizina labradus

- Pacific golden orb weaver[71]