The Celtic harp is a triangular frame harp traditional to the Celtic nations of northwest Europe. It is known as cláirseach in Irish, clàrsach in Scottish Gaelic, telenn in Breton and telyn in Welsh. In Ireland and Scotland, it was a wire-strung instrument requiring great skill and long practice to play, and was associated with the Gaelic ruling class. It appears on Irish coins, Guinness products, and the coat of arms of the Republic of Ireland, Montserrat, Canada and the United Kingdom.

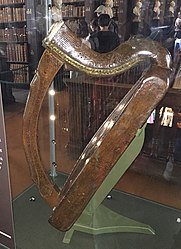

'Brian Boru's harp' (Cláirseach Brian Bóramha) on display in the Library of Trinity College Dublin | |

| String instrument | |

|---|---|

| Other names | cláirseach, clàrsach, telyn, telenn[1] |

| Classification | |

| Hornbostel–Sachs classification | 322.221 (manually tuned frame harp) |

| Related instruments | |

| Irish harping | |

|---|---|

| Country | Ireland |

| Reference | 01461 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 2019 (14th session) |

| List | Representative |

Early history

The early history of the triangular frame harp in Europe is contested. The first instrument associated with the harping tradition in the Gaelic world was known as a cruit. This word may originally have described a different stringed instrument, being etymologically related to the Welsh crwth. It has been suggested that the word clàrsach / cláirseach (from clàr / clár, a board) was coined for the triangular frame harp which replaced the cruit, and that this coining was of Scottish origin.[2]

A notched piece of wood which some have interpreted to be part of the bridge of an Iron Age lyre dating to around 300 BC was discovered on the Isle of Skye, which, if actually a bridge, would make it the oldest surviving fragment of a western European stringed instrument[3][4] (although images of Greek lyres are much older). The earliest descriptions of a European triangular framed harp, i.e. harps with a fore pillar, are found on carved 8th century Pictish stones.[5][6][7][8][9][10] Pictish harps were strung from horsehair. The instruments apparently spread south to the Anglo Saxons who commonly used gut strings and then west to the Gaels of the Highlands and to Ireland.[11][12][13][14] Exactly thirteen depictions of any triangular chordophone instrument from pre-11th-century Europe exist and twelve of them come from Scotland.[15]

The earliest Irish references to stringed instruments are from the 6th century, and players of such instruments were held in high regard by the nobility of the time. Early Irish law from 700 AD stipulates that bards and 'cruit' players should sit with the nobility at banquets and not with the common entertainers. Another stringed instrument from this era was the tiompán, most likely a kind of lyre. Despite providing the earliest evidence of stringed instruments in Ireland, no records described what these instruments looked like, or how the cruit and tiompán differed from one another.[16]

Only two quadrangular instruments occur within the Irish context on the west coast of Scotland and both carvings date two hundred years after the Pictish carvings.[14] The first true representations of the Irish triangular harp do not appear till the late eleventh century in a reliquary and the twelfth century on stone and the earliest harps used in Ireland were quadrangular lyres as ecclesiastical instruments,[9][14][17] One study suggests Pictish stone carvings may be copied from the Utrecht Psalter, the only other source outside Pictish Scotland to display a Triangular Chordophone instrument.[18] The Utrecht Psalter was penned between 816 and 835 AD.[19] However, Pictish Triangular Chordophone carvings found on the Nigg Stone date from 790 to 799 AD.[20] and pre-date the document by up to forty years. Other Pictish sculptures also predate the Utrecht Psalter, namely the harper on the Dupplin Cross from c. 800 AD.

The Norman-Welsh cleric and scholar Gerald of Wales (c.1146 – c.1223), whose Topographica Hibernica et Expugnatio Hibernica is a description of Ireland from the Anglo-Norman point of view, praised Irish harp music (if little else), stating:

The only thing to which I find that this people apply a commendable industry is playing upon musical instruments… they are incomparably more skilful than any other nation I have ever seen[21]

However, Gerald, who had a strong dislike of the Gaelic Irish, somewhat contradicts himself. While admitting that the style of music originated in Ireland, he immediately added that, in "the opinion of many", the Scots and the Welsh had now surpassed them in that skill.[22][23][24] Gerald refers to the cythara and the tympanum, but their identification with the harp is uncertain, and it is not known that he ever visited Scotland.[25]

Scotland and Wales, the former by reason of her derivation, the latter from intercourse and affinity, seek with emulous endeavours to imitate Ireland in music. Ireland uses and delights in but two instruments, the harp namely, and the tympanum. Scotland uses three, the harp, the tympanum, and the crowd.

Early images of the clàrsach are not common in Scottish iconography, but a gravestone at Kiells, in Argyllshire, dating from about 1500, shows one with a typically large soundbox, decorated with Gaelic designs.[27] The Irish Saint Máedóc of Ferns reliquary shrine dates from c.1100, and clearly shows King David with a triangular framed harp including a "T-Section" in the pillar.[28] The Irish word lamhchrann or Scottish Gaelic làmh-chrann came into use at an unknown date to indicate this pillar which would have supplied the bracing to withstand the tension of a wire-strung harp.

Three of the four pre-16th-century authentic harps that survive today are of Gaelic provenance: the Brian Boru Harp in Trinity College, Dublin, and the Queen Mary and Lamont Harps, both in the National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh.[29] The last two are examples of the small low-headed harp, and were long believed to have been made from hornbeam, a wood not native to Scotland or Ireland.[30] This theory has been refuted by Karen Loomis in her 2015 PhD thesis.[31] All three are dated approximately to the 15th century and may have been made in Argyll in western Scotland.[32][33]

One of the largest and most complete collections of 17th–18th century harp music is the work of Turlough O'Carolan, a blind, itinerant Irish harper and composer. At least 220 of his compositions survive to this day.

Characteristics and function

Two experts in this field, John Bannerman and Micheal Newton, agree that, by the 1500s, the most common Celtic harp strings are made of brass.[34][2] Historical sources don't seem to mention the strings' gauge or materials, other than references to a very low-quality and simply-made brass, often contemporarily called "red brass." Modern-day experiments on stringing a Celtic harp include testing of more exotic and custom materials including copper alloys, silver, and gold. Other experiments include more easily obtainable materials, including softer iron, as well as yellow and red brass.[35] The strings attach to a soundbox, typically carved from a single log, commonly of willow, although other woods, including alder and poplar, have been identified in extant harps. The Celtic harp also had a reinforced curved pillar and a substantial neck, flanked with thick brass cheek bands. The strings are plucked with long fingernails.[36] This type of harp is also unique amongst single row triangular harps in that the first two strings tuned in the middle of the gamut were set to the same pitch.[37]

Components

The names of the components of the cláirseach were as follows:[38][39]

| Irish | Scottish Gaelic | English |

|---|---|---|

| amhach | amhach | neck |

| cnaga | cnagan | pins |

| corr | còrr | pin-board |

| com | com | chest or soundbox |

| lámhchrann | làmh-chrann | tree or forepillar |

| téada | teudan | strings |

| crúite na dtéad | cruidhean nan teud | string shoes |

| fhorshnaidhm | urshnaim | toggle |

The corr had a brass strap nailed to each side, pierced by tapered brass tuning pins. The treble end had a tenon which fitted into the top of the com (soundbox). On a low-headed harp the corr was morticed at the bass end to receive a tenon on the lámhchrann; on a high-headed harp this tenon fitted into a mortice on the back of the lámhchrann.

The com (soundbox) was usually carved from a single piece of willow, hollowed out from behind. A panel of harder timber was carefully inserted to close the back.

Crúite na dtéad (string shoes) were usually made of brass and prevented the metal strings from cutting into the wood of the soundbox.

The fhorshnaidhm may refer to the wooden toggle to which a string was fastened once it had emerged from its hole in the soundboard.

Playing technique

The playing of the wire-strung harp has been described[by whom?] as extremely difficult. Because of the long-lasting resonance, the performer had to dampen strings which had just been played while new strings were being plucked, and this while playing rapidly. Contrary to conventional modern practice, the left hand played the treble and the right the bass. It was said[by whom?] that a player should begin to learn the harp no later than the age of seven. The best modern players have shown, however, that reasonable competence may be achieved even at a later age.

Social function and decline

During the medieval period, the wire-strung harp was in demand throughout the Gaelic territories, which stretched from the northern Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland to the south of Ireland. The Gaelic worlds of Scotland and Ireland, however, while retaining close links, were already showing signs of divergence in the sixteenth century in language, music and social structure.

The harp was the aristocratic instrument of Gaelic Ireland, and harpers enjoyed a high social status which was codified in Brehon Law.[16] The patronage of harpers was adopted by Norman and British settlers in Ireland until the late 18th century, although their standing in society was greatly diminished with the introduction of the English class system. In his biography of Turlough O'Carolan, historian Donal O'Sullivan writes:

We may note as a remarkable fact that the descendants of Protestant settlers, who had been at most for three generations in the country, seem to have been just as devoted to the Irish music of the harp as were the old Gaelic families.[40]

The function of the clàrsach in a Hebridean lordship, both as entertainment and as literary metaphor, is illustrated in the songs of Màiri Nic Leòid (Mary MacLeod) (c. 1615–c. 1705), a prominent Gaelic poet of her time. The chief is praised as one who is skilled in judging harp-playing, the theme of a story and the pith of sense:

- Tuigsear nan teud,

- Purpais gach sgèil,

- Susbaint gach cèill nàduir.[41]

The music of harp and pipe is shown to be intrinsic to the splendour of the MacLeod court, along with wine in shining cups:

- Gu àros nach crìon

- Am bi gàirich nam pìob

- Is nan clàrsach a rìs

- Le deàrrsadh nam pìos

- A' cur sàraidh air fìon

- Is 'ga leigeadh an gnìomh òircheard.[42]

Here the great Highland bagpipe shares the high status of the clàrsach. It would help supplant the harp, and may already have developed its own classical tradition in the form of the elaborate "great music" (ceòl mòr). An elegy to Sir Donald MacDonald of Clanranald, attributed to his widow in 1618, contains a very early reference to the bagpipe in a lairdly setting:

- Is iomadh sgal pìobadh

- Mar ri farrum nan dìsnean air clàr

- Rinn mi èisdeachd a’d' bhaile... [43]

There is evidence that the musical tradition of the clàrsach may have influenced the use and repertoire of the bagpipe. The oral mnemonic system called canntaireachd, used for encoding and teaching ceòl mòr, is first mentioned in the 1226 obituary of a clàrsair (harp player). Terms relating to theme and variation on the clàrsach and the bagpipe correlate to each other. Founders of bagpipe dynasties are also noted as clársach players.[43]

The names of a number of the last harpers are recorded. The blind Duncan McIndeor, who died in 1694, was harper to Campbell of Auchinbreck, but also frequented Edinburgh. A receipt for "two bolls of meall", dated 1683, is extant for another harper, also blind, named Patrick McErnace, who apparently played for Lord Neill Campbell. The harper Manus McShire is mentioned in an account book covering the period 1688–1704. A harper called Neill Baine is mentioned in a letter dated 1702 from a servitor of Allan MacDonald of Clanranald. Angus McDonald, harper, received payment on the instructions of Menzies of Culdares on 19 June 1713, and the Marquis of Huntly's accounts record a payment to two harpers in 1714. Other harpers include Rory Dall Morison (who died c. 1714), Lachlan Dall (who died c. 1721–1727), and Murdoch MacDonald (who died c. 1740).[44]

By the middle of the eighteenth century the "violer" (fiddle player) had replaced the harper, a consequence, perhaps, of the growing influence in the Gaelic world of Lowland Scots culture.[44]

Revival

In the early 19th century, even as the old Gaelic harp tradition was dying out, a new harp was developed in Ireland.[45] It had gut strings and semitone mechanisms like an orchestral pedal harp, and was built and marketed by John Egan, a pedal harp maker in Dublin.

The new harp was small and curved like the historical cláirseach or Irish harp, but it was strung with gut and its soundbox was lighter.[46] In the 1890s a similar new harp became popular in Scotland as part of a Gaelic cultural revival.[47]

There is now, however, renewed interest in the wire-strung harp, or clàrsach, with replicas being made and research being conducted into ancient playing techniques and terminology.[48] A notable event in the revival of the Celtic harp is the Edinburgh International Harp Festival, which has been held annually since 1982 and includes both performances and instructional workshops.[49]

Bibliography

References

External links

- Historical Harp Society of Ireland

- An Chúirt Chruitireachta, International traditional harp course held annually in Termonfeckin Co. Louth, Ireland Archived 13 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- The Clarsach Society/Comunn na Clarsaich, resource centre for the Scottish harp

- Edinburgh International Harp Festival

- List of surviving early Gaelic harps

- Historic wire-strung harps and harpers listed and described on wirestrungharp.com

- Gaelic Modes Web articles on Gaelic harp harmony and modes

- Treasures of early Irish art, 1500 B.C. to 1500 A.D., an exhibition catalogue from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which contains material on Clàrsach (cat. no. 68)

- Asni: harp lore – descriptions of several types of historical European harps (with sound samples)

- The Celtic Harp Page – information on Celtic and other types of harps

- My Harp's Delight – learning to play the Celtic harp, tips and techniques, buying a harp

- Teifi Harps – Celtic & Folk Harps in Wales

- "Tears, Laughter, Magic" – An Interview with Master Celtic Harp Builder Timothy Habinski on AdventuresInMusic.biz, 2007

- Celtic Harp Amplification Series – using microphones and guitar amplifiers with folk harps

- Markwood Strings – Information on installing harp strings, harp string installation guide

- [1] Early Gaelic Harp site by Simon Chadwick